Exam Support

Carbon Emissions Trading - Exam Question Walkthrough for Edexcel A-Level Economics

- Level:

- A-Level

- Board:

- Edexcel

Last updated 12 Apr 2021

Carbon emissions trading is the focus of this 15-mark answer walk through for EdExcel Economics.

Extract 1: The EU Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme

The EU emissions trading scheme (ETS) covers more than 11,000 power stations and industrial plants across the EU. The system covers approximately 40% of the EU’s emissions, from the power sector, manufacturing industry, and aviation.

The emissions cap decreases over time (1.7% each year) to reduce overall emissions. 154 airlines operating between the 31 countries are covered within the ETS but via a separate cap. Approximately 140 UK aircraft operators take part in the ETS

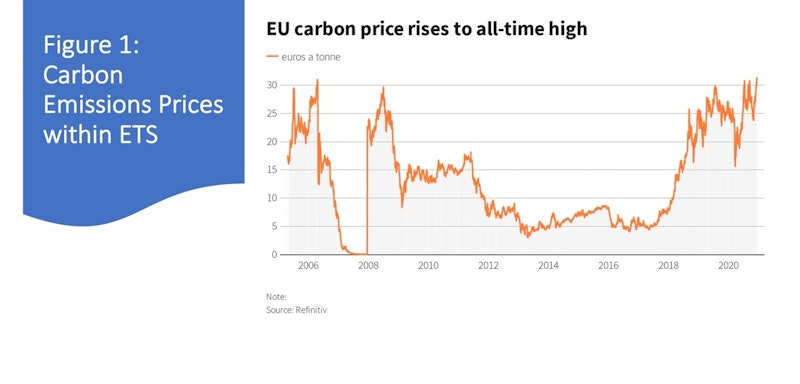

The market price of emissions allowances fell dramatically after the global financial crisis in 2008 and stayed low for several years. From 2011 until 2017, carbon permits cost less than €10 per tonne although in 2018 the price started to rise, reaching over €28 in 2019.

In the earlier years, several Member States considered the EU carbon price to be too low to create a strong enough incentive for polluters to undertake the required investment in low-carbon technologies and to drive low-carbon innovation.

Source: UK Parliamentary Reports

KAA Point 1:

Negative externalities such as CO2 emissions from the 140 UK airlines mentioned in Extract 1 lead to market failure if emitters fail to consider the external costs of supply leading to over-production and a deadweight loss of social welfare. Carbon trading uses the market mechanism to change relative prices and the incentives of producers and consumers to alter their behaviour to reduce carbon emissions. As the cap (supply) of tradable permits is lowered (Extract 1 says that the cap is lowered by 1.7% per year) then, ceteris paribus, the market price of emissions permits will rise. This increases the internal cost to producers and – in theory – creates a stronger signal for them to invest in low carbon technologies and find other ways of reducing pollution. In this way, emissions trading puts a price on each tonne of carbon, helps to internalise externalities and therefore addresses market failure.

Evaluation Point 1:

Whilst in theory carbon trading can be effective in reducing pollution and helping to correct for market failures, in practice, as we see from Figure 1, the price of carbon permits inside the EU’s ETS has been highly volatile with the price ranging from Euro 30 to close to zero since the platform was established in 2006. Indeed, Extract 1 says that from “2011 until 2017, carbon permits cost less than €10 per tonne” which means that polluters faced little if any incentive to bring forward investment in low-carbon technologies. If the social cost of carbon (SC = private cost + external cost) is – for example – estimated in a range Euro 50 to Euro 100, then the market is simply not working optimally to changes incentives and behaviour. This is likely due to an over-supply of carbon permits which itself can be seen as an example of government or regulatory failure.

KAA Point 2:

A second argument in favour of carbon trading is that as the market price of a carbon permit increases, then this send a signal via the price mechanism. A high price per unit of CO2 should cause a shift in demand away from dirtier fossil fuels (such as power stations mentioned in Extract 1) towards cleaner renewable energy. This is especially the case for the most heavily-polluting power generators since they must buy many more carbon permits each year to continue operating and avoid heavy fines. In contrast, renewable energy providers will create less pollution and each CO2 permit will be more valuable to them. In this system, trading permits allows firms to choose where and when to reduce their emissions – many will choose the cheapest abatement options first. Permit prices will also reflect macroeconomic conditions – falling sharply (as Figure 1 shows – falling close to zero) during the recession caused by the Global Financial Crisis. This provides welcome flexibility and should help to protect some jobs during a downturn when business revenues and profits are under pressure.

Evaluation Point 1:

In evaluation, carbon trading on its on is unlikely to be sufficient to address market failures from pollution in part because once traded, the price per tonne is too variable. Contrast this with the main alternative which is a carbon tax where the price can be set and fixed closer to the estimated social cost of capital (likely to be much higher than shown in Fig.1) and which also generates tax revenues for a government which can be then be hypothecated to fund clean energy projects or use as a rebate to those affected such as lower income consumers. Making the polluter pay via a carbon tax and using extra tax revenues wisely to promote research can address two market failures in one go especially if research tends to be under-provided by the market mechanism.

You might also like

Green Growth Indicators

16th October 2015

Agriculture and economic development

Study Notes

Scottish government launches prize to drive innovation in tidal power

10th February 2019

Dynamic efficiency - the search for better batteries

9th April 2021

Government intervention - Paris announces car ban for central districts

23rd February 2022

Energy Price Crisis - What Future for Nuclear Power in the UK?

14th August 2022

Daily Email Updates

Subscribe to our daily digest and get the day’s content delivered fresh to your inbox every morning at 7am.

Signup for emails