Study Notes

Can the UK reach full-employment?

- Level:

- AS, A-Level, IB

- Board:

- AQA, Edexcel, OCR, IB, Eduqas, WJEC

Last updated 20 Jan 2019

Unemployment in the UK, as measured by the Labour Force Survey, has declined to a forty-five year low of just 4.2% of the labour force. This has encouraged hopes that Britain can get close to full-employment.

The modern definition of full-employment is where the number of people in short-term (frictional) unemployment is equivalent to the stock of registered job vacancies.

Presently, there are around 800,000 unfilled vacancies (although this figure may be an underestimate) and LFS unemployment is 1.4 million. Employment is at a record high and there has also been a significant improvement in labour market participation rates for both genders over the last decade.

Some economists argue that the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (or NAIRU) which tracks the jobless rate consistent with a stable inflation rate may have fallen to four percent of less. Once more, this is evidence to support the view that full-employment is no longer an objective locked away only in the economics textbooks.

Since the end of the last recession, UK unemployment has more than halved at a time when the total economically-active labour force has also grown. But nudging unemployment below the landmark 4 percent mark will likely prove difficult. This is because there is a core level of joblessness associated with frictional and structural unemployment (remember that the data is already seasonally adjusted).

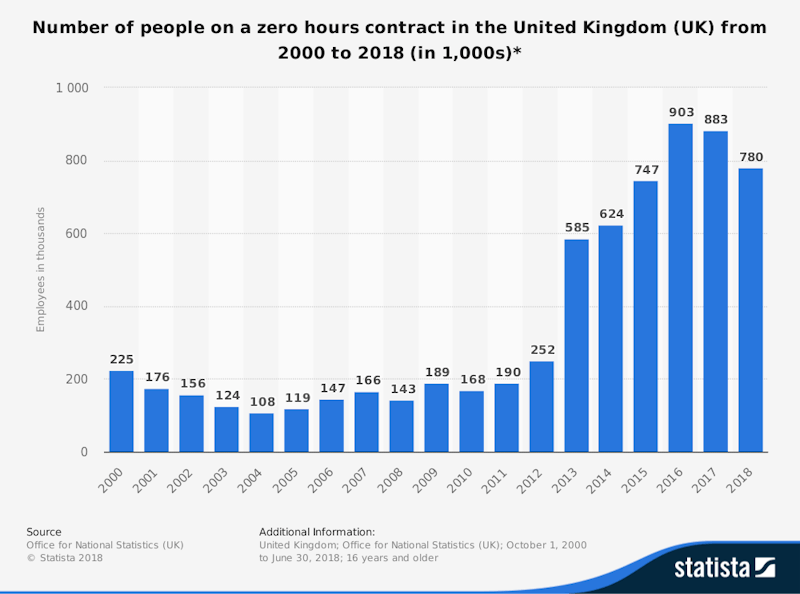

What are the main barriers in the way of getting to full employment? Most relate to the factors impeding the occupational and geographical mobility of labour. And there are deep-rooted issues with work incentives some of which reflect the complexity of the tax and benefit system whilst others flow from the ever-changing nature of work and the shift towards flexible employment (including zero-hours contracts) and the decline of trade union negotiating power than has led to a rise in in-work poverty.

Barriers to reducing unemployment further include the following:

Regional unemployment

Significant regional differences in unemployment and employment opportunities - the gap between regions with the highest unemployment and richer, more affluent areas has narrowed in the last ten years but remains persistently large. Many economists want increased funding for and a commitment to a more activist regional and industrial policy to generate more full-time and well paid jobs in regions of relative decline. London and the South East continue to attract net inflows of new entrants into the labour market whereas coastal regions and areas traditionally dependent on public sector jobs and heavy industry have lagged behind. That said, there are often sizeable variations in job opportunities within as well as between regions. Indeed Greater London has an unemployment rate (4.8% of the labour force in September 2018) which is higher than the UK average. In Northern Ireland, the employment rate of 69.3% is the lowest in the UK contrasted with 79.2% in the South West.

The challenge of getting the long-term unemployed (LTU) back into work

Some significant progress has been made in lowering the rate of long-term unemployment - defined as people out of paid work for at least one year. Most long-term unemployment is structural, the result of the unemployed having skills and experience that do not readily match the requirements of jobs in a constantly-evolving labour market. Being out of work for a lengthy period reduces the motivation to search for a new job and can lead to the depreciation of human capital. The long-term jobless can become outsiders in the jobs market. In the UK at present, around 1.2% of the labour force have been out of work for more than a year. This is down from 2.3% in 2013 and there are signs of some successes in government initiatives to get these people back into formal employment (including the cut in employers national insurance for firms who take on a LTU worker).

Housing affordability

It is widely recognised that the UK housing market is a barrier to people being able to move in search of fresh work. In the Spring of 2018, on average, full-timer workers could expect to pay nearly eight times their earnings from work on buying a home in England and Wales. In parts of London, for example Kensington and Chelsea, media house prices are between 30-40 times median workplace earnings. Little wonder that housing affordability has worsened over the last ten years.

As it has become harder to afford a mortgage, many have been required to rent and surging demand has also pushed upmarket rents in the private sector. According to Hometrack, the average cost of renting in England and Wales increased by 20% between 2007 and 2017 whilst real wages have fallen or stagnated. Average rents were £1,500 per calendar month in London contrasted with £544 per month in the North East. This trend has increased the amount of money that people needing to rent must put aside and has cut their effective disposable income. Little wonder that more people are staying at home with their parents and guardians. Demand for social housing has also grown at a time when new building of affordable social properties has remained weak.

The housing sector in the UK allied to the rising cost of commuting (with many rail fares rising faster than inflation) has acted as a major barrier to the geographical mobility of labour and has contributed to the growth of in-work poverty.

Skills shortages

Across the world in both advanced and developing/emerging countries, the pace of change in labour markets continues to accelerate. Nearly ten years on from the last recession, the level of cyclical unemployment has fallen but structural unemployment due to the mis-match of skills to jobs continues to challenge policy-makers. Many surveys point to continuing problems in attracting workers with the right blend of skills, experience and attitudes. A survey from the Open University published in September 2018 found that employers in the UK spent over £6 billion in 2017 to combat a shortage of required skills - including recruitment fees and taking on temporary labour. Brexit uncertainty and signs of a sharp fall in net inward migration from other EU countries may make this worse in the near term. The UK Government introduced the apprenticeship levy in 2016 which is a tax on UK employers which can be used to fund apprenticeship training. This has to be paid by all firms with a payroll in excess of £3 million a year and the hope is that, over time, it will increased the number of 16-18 year olds taking recognised technical level (vocational) qualifications to improve the human capital of the labour force and bring down further the rate of youth unemployment.

The low wage economy

To what extent is further progress towards full employment dependent on reforming the flexibility of the UK labour market? Or is flexibility essential to keeping the employment rate high from one cycle to another? There are good reasons to welcome flexibility in hours - they suit people wanting to study or who have caring requirements in our ageing population. But whilst unemployment has fallen well below 5 percent, labour productivity growth remains stagnant and real wages have declined for many people. In-work poverty has grown, indeed the Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimate that over half of families living in relative poverty (defined as an income < 60 percent of the median) have at least one person in work. Low wages keep families dependent on one or more benefits and they don’t allow families to save (indeed, their exposure to high interest rate unsecured debt is rife). From a Keynesian perspective, raising productivity and wages is important to lift household spending and saving whilst giving the UK government finances a helping hand as tax revenues grow and welfare claims diminish.

Overview

There are other barriers to getting unemployment down without risking an acceleration in wage and price inflation. Whilst we tend to focus on the aggregate numbers for unemployment and employment, it is important to remember what lies beneath this data not least the employment challenges facing the young, those with low educational attainment, ethnic groups and communities that have become on the fringe of a more prosperous society. The unemployment rate is a key macroeconomic indicator, but macroeconomics has micro-foundations. We need to understand the complexities of the labour market to design policies and change incentives to sustainably bring even more people back into work.

You might also like

Macroeconomic Objectives and Conflicts (Revision Presentation)

Teaching PowerPoints

Geographical immobility of the low skilled workforce

30th March 2015

Germany's Labour Market Miracle

27th August 2015

What is the Output Gap?

Study Notes

Unemployment and Inflation in the UK Economy

Topic Videos

Economies of Ale - Changes to the UK Pub Industry

27th November 2018

What is disguised unemployment?

Study Notes

Critique of Keynesian Economics

Study Notes

Daily Email Updates

Subscribe to our daily digest and get the day’s content delivered fresh to your inbox every morning at 7am.

Signup for emails