In the News

Lessons from the collapse of Carillion

18th January 2018

What can we read into the collapse of Carillion? It is clearly a story with many, many different aspects; here are a few thoughts about where it touches the syllabus for our Business students.

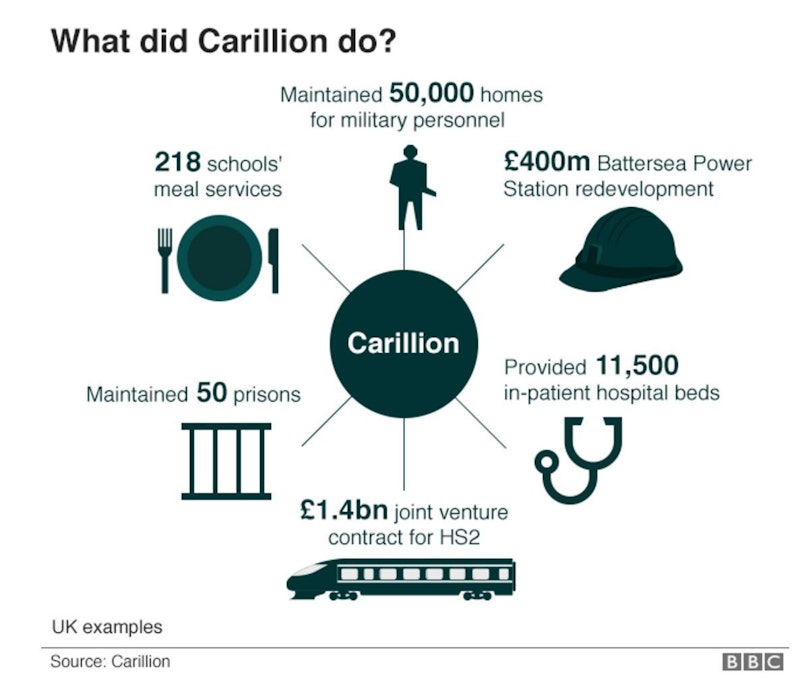

First, was the company simply too big? Carillion started as the result of a demerger of Tarmac in 1999. Tarmac focused on its core heavy building materials business, while Carillion included the former Tarmac Construction contracting business and the Tarmac Professional Services group of businesses. Over the next ten years or so it expanded fast, using horizontal integration to buy other large construction services and contracting firms such as Mowlem, McAlpine and John Laing. Now it employs 43,000 staff globally, around half of them in the UK where it does most of its business. It also operates in Canada, the Middle East and the Caribbean. The BBC have identified just a few examples of their tasks in the UK:

They also operate customer service centres for businesses that want to outsource their call centre operations, power transmission and distribution, and telecommunications. They list the sectors they work in, including aviation, healthcare, education, local and central government, finance, oil and gas, commercial retail residential and leisure, and defence.

So one question to ask is whether the scale and scope of the organisation was too large, and it suffered diseconomies of scale as the business was too big for efficient co-ordination, communication and control.

Secondly, was the gearing ratio much too high? It is widely reported that when it went into liquidation on Monday, it had just £29mn in the bank (current assets) and debts of around £1.5bn. Even back in July, before the share price collapsed, its market value based on the share price was only £1bn; by Monday this had fallen to £61million. Their 2016 balance sheet shows total net assets of just over £700mn, but that includes intangible assets of over £1.6bn, and a liability of £66mn to the pension fund.

What was happening to profit ratios? Well, the 2016 income statement shows us that revenue in its main areas of operations, from Private Public Partnerships in the UK (that's the widely reported work for government on building hospitals, motorway and rail infrastructure projects and so on) and from construction in the Middle East was rising, operating profit from those fell by 43% and 36% respectively. Although its biggest revenue earner is Support Services, and profit there grew by 25%, group reported profit before tax fell by 5% in 2016 - not a good sign.

Then, over-optimism in its accounting. Using the 2016 report and accounts again, it is noticeable that the financial highlights pages consistently celebrate 'Order book plus probably orders' and 'Pipeline of contract opportunities' as amongst the group's key advantages. How many of those 'probable' orders actually came through?

The fallout is clearly going to have a massive effect on all the stakeholders. Not only on the investors in Carillion, workers facing uncertainty over their jobs and managers losing bonuses, but also patients at hospitals where construction work is on hold until the contracts are sorted out, banks who lent money to them and face bad debts, competitors who are scrambling to take up the contracts to run prisons, provide school meals or operate call centres. And, the subject of many news reports, the small businesses supplying the services that Carillion contracted out, who are not being paid and suffering cash flow crises that threaten to close them down.

I imagine there will be many, many aspects of this story still to come to light, and it will be a case study that is used across the Business syllabus for a long time.

You might also like

Stakeholders (Introduction)

Study Notes

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Topic Videos

The VW Scandal and the Car Industry

28th September 2015

Ryanair - the gift that keeps on giving

22nd September 2017

Executive pay - taking a wider view

6th December 2017

How Stakeholders are Affected by Bank Closures

9th January 2018

Stakeholders and Stakeholder Mapping

Topic Videos

Daily Email Updates

Subscribe to our daily digest and get the day’s content delivered fresh to your inbox every morning at 7am.

Signup for emails